The case of Johannes Hendricus Maria Smit v EUIPO, currently pending before the EUIPO’s Grand Board of Appeal, raises a question that sits at the intersection of personality rights, branding strategy, and EU trade mark law: can a photorealistic image of a human face function as a trade mark? The anticipated judgment may prove to be one of the more consequential decisions in recent years on the registrability of non-traditional signs.

Background

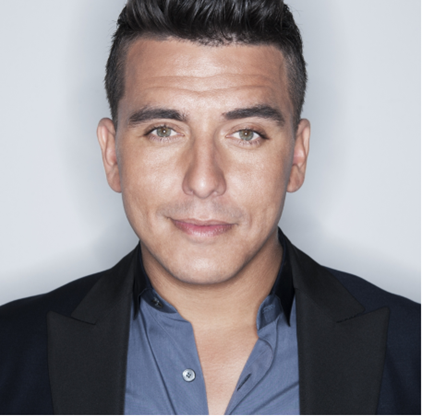

Mr Jan Smit, a prominent Dutch singer and television presenter, applied on 23 October 2015 to register a figurative mark comprising a high-resolution image of his own face. The application covered a broad range of goods and services in Classes 9, 16, 24, 25, 35 and 41. These included musical recordings, printed matter, textiles, apparel, advertising and live entertainment.

The image was not stylised or abstracted. It was a direct, photorealistic likeness of Mr Smit, as shown below (for those who wish to view the application, it can be seen here).

Image source (https://euipo.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/014711907)

In this respect, especially that the mark consisted essentially of the whole recognizable person of Mr Smit himself (to those who know him, or know of him), it differed markedly from the kinds of logos, monograms or caricatures of known persons more commonly encountered in the register.

The Inital Examination

In a decision issued on 19 December 2023, the EUIPO Examination Division refused the application. The examiner found that the mark was devoid of distinctive character under Article 7(1)(b) of the EU Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR) and was descriptive under Article 7(1)(c).

The Office held that a realistic image of a person’s face, without any distinctive stylisation or accompanying verbal element, would be perceived by the average consumer merely as a decorative or promotional feature. It would not be seen as an indication of trade origin.

Second Board of Appeal

Mr Smit appealed the refusal before the Second Board of Appeal. In support of the appeal, he pointed to prior EUIPO practice, including a notable case in which the photorealistic image of Dutch fashion model Maartje Verhoef had been accepted for registration. He also submitted that his image, though realistic, had acquired distinctiveness through long-standing commercial use in connection with the goods and services claimed.

Referral to the Grand Board of Appeal

The Second Board of Appeal acknowledged a degree of inconsistency in the Office’s approach to image-based trade marks and referred the case to the Grand Board of Appeal on 26 September 2024. The referral was made on grounds of legal uncertainty and the need to clarify the standard applicable to this category of signs.

Three key provisions of the EUTMR are central to this case:

- Article 7(1)(b): prohibits the registration of marks which are devoid of distinctive character.

- Article 7(1)(c): excludes signs which consist exclusively of indications which may serve to designate characteristics of the goods or services.

- Article 7(3): provides an exception for signs which have acquired distinctiveness through use prior to the filing date.

The Grand Board is expected to provide guidance not only on the threshold for inherent distinctiveness but also on the evidential requirements for acquired distinctiveness in the context of personal imagery.

Mr Smit contends that the image in question is clearly recognisable as his own and that, within certain Member States, it is closely associated with his commercial output. The mark, he argues, is not generic but individual and specific. It is a face that already functions as a brand.

His representatives submitted that the image has appeared for many years on albums, promotional materials, licensed merchandise and various advertising campaigns. They argued that in the relevant sectors, the public already regards the image as an indication of commercial origin.

They further challenged what they saw as an overly formalistic and unduly rigid interpretation of distinctiveness by the Examination Division, particularly in light of prior registrations involving similarly realistic images.

Observations by INTA

In January 2025, the International Trademark Association (INTA) submitted third-party observations in support of the applicant. INTA argued that photorealistic depictions of human faces are not inherently incapable of functioning as trade marks. Whether they do so in practice must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, having regard to the actual use and market perception of the sign.

INTA also cautioned against any blanket rule which would exclude photographic portraits from registrability. Instead, they called for a more nuanced framework, one which balances the legal criteria of distinctiveness with the commercial realities of modern personal branding.

The case raises several unresolved questions within EU trade mark law:

- Can a naturalistic human face be considered inherently distinctive without stylisation?

- Is recognition within part of the EU sufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness?

- What level of fame or renown is required before a personal image is treated as a sign of commercial origin?

- Should the Office develop a clearer doctrine to guide applications involving image rights?

The answers to these questions may have lasting implications not only for entertainers and public figures but also for sports personalities, influencers and other individuals who rely on their image for brand value.

In the meantime: across the Channel

While the EU has thus far taken a cautious approach to face-based marks, other jurisdictions have shown more flexibility. In the United States, the image of Colonel Sanders (famous for KFC chicken) has long been registered as a trade mark. In the United Kingdom, the test remains whether the sign is perceived as an indicator of origin by a significant portion of the relevant public. In both cases, stylisation is often helpful but not necessarily essential.

For example, the UKIPO has accepted and allowed Cole Palmer’s face mark to proceed to registration in relation to a broad specification. You can view the application UK00004129121 here.

A judgment from a sound authority such as the Grand Board of Appeal will ideally foster greater harmonisation across jurisdictions over the same issue. There could be clearer guidelines, for example, in sectors where face imagery is commonplace, should a face sign depart significantly from the norms before consumers read it as a badge of origin rather than mere decoration?

Although well-known faces are more likely to be distinctive, Palmer’s very broad specification goes beyond what he is known for, so acquired distinctiveness may be needed. This raises a filing-policy question: should face marks be confined to merchandising in closely connected classes, and what is the right test? Would, for example, David Beckham’s face be registrable only for football merchandise, or for a wider range because merchandising naturally straddles categories? And do the SkyKick principles bite here, so when is an excessively broad specification vulnerable to a bad-faith challenge where there is no genuine intention to use? Does it go without saying that the face of a footballer won’t promote goods that are not often connected with that sport, for example, spare parts for audio equipment?

Conclusion

A clear EU judgment would be welcome to set a precedent within the EU and provide persuasive authority for other jurisdictions, including the UK. The forthcoming decision will determine whether the Grand Board will align with this more permissive practice in other jurisdictions (which despite being permissive don’t have in-depth guidelines) or reaffirm the need for legal certainty and adopt a more conservative approach. At the end of 2026 this area of the law will hopefully have developed a lot further.

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/SearchServiceImages/2026-03-02-09-25-03-360-69a5576f843c161e183b0e4f.jpg)

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/SearchServiceImages/2026-02-26-15-54-56-695-69a06cd03a6e69b01f61e487.jpg)

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/SearchServiceImages/2026-02-25-16-00-40-354-699f1ca8de0dd5cefa7018ad.jpg)