I have recently visited the “Marie Antoinette Style” exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The show is a stunning exploration of how the popular Queen still shapes pop culture, film and fashion.

The exhibition brings together more than twenty objects from Versailles, which are being displayed in the UK for the first time. Among them are paintings, furniture, jewellery, and personal items that once belonged to Marie Antoinette herself. These include a remarkably small pair of shoes that reminds us of just how young she was when she became Queen.

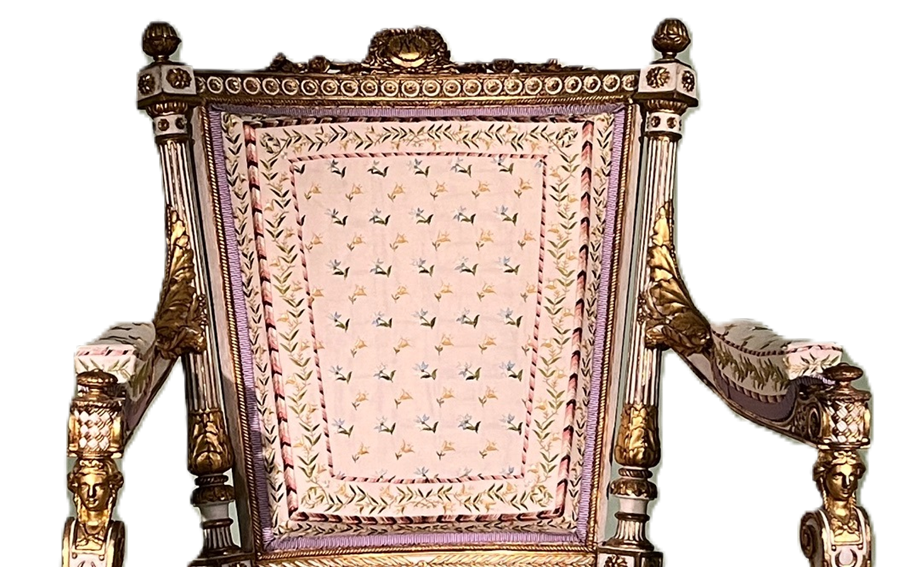

Image source: Author's own photo - Marie Antoinette's armchair, V&A London.

Her monogram evokes luxury and refinement. Maybe it's my trade mark attorney brain, but all I could think about while wandering through the exhibition was that this is an early form of branding.

In the UK, various businesses have attained protection for trade marks containing “Marie Antoinette” covering goods such as jewellery, clothing, and cosmetics, among others, evidently capitalising on the luxury associations still linked to the Queen.

The consistent use of the Queen's monogram resonates strongly with the principles behind trade mark protection. A brand carries the reputation and ethos of a business. Maintaining this requires vigilance, consistency, and enforcement when needed.

Marie Antoinette's brand identity has inspired filmmakers such as Sofia Coppola, and major fashion houses whose creative works feature in the exhibition. These include couture pieces by Vivienne Westwood, Dior, Chanel and Manolo Blahnik (the latter sponsored the exhibition and designed many of the shoes worn by Kirsten Dunst in Coppola's aforementioned film).

This exhibition is as culturally rich as it is intellectual-property-drenched: a reminder that brand identity endures when it is treated and protected as valuable property.

Her aesthetic endures because it is elastic: it can mean excess, rebellion, tragedy, artifice, youth, death

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-23-14-48-29-276-699c68bd6c71a5b1b464adc4.png)

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/SearchServiceImages/2026-02-23-11-11-43-181-699c35ef1c5ffffe86dbe5d1.jpg)

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/SearchServiceImages/2026-02-20-16-34-28-315-69988d14842a7bc7f01e87a0.jpg)