- the implications of using CAD images in design registration drawings

- guidance on the validity of later designs over earlier designs owned by the same entity; and

- the test for unregistered design infringement and the assessment of what constitutes a “part”

Schnuggle’s most successful product is a baby bath product, which includes a “bum-bump” the purpose of which to prevent a baby from sliding down the bath and underneath the surface of the water. Schnuggle owned two Registered Community Designs (RCDs) in respect of its baby bath product. The first was filed in 2013 and sought to protect the original design. The second RCD was filed in 2015 and Schnuggle submitted that it was filed to protect the latest version of the product, which incorporated a number of changes from the original design.

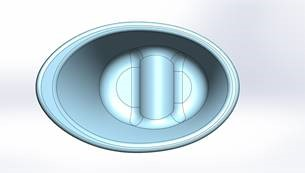

RCD No. 00224196-001 (RCD-196). A selection of the images used in RCD-196 are set out below:

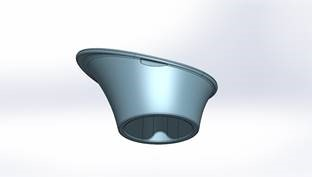

RCD No. 002616763-0001 (RCD-763). A selection of the images used in RCD-763 are set out below:

.jpg.png)

.jpg.png)

.jpg.png)

Upon becoming aware of a similar product marketed by Munchkin, Schnuggle brought proceedings for registered design infringement, relying upon RCD-196 and RCD-763, in addition to UK unregistered design right infringement. An image of the Munchkin “Sit and Soak” baby bath is set out below:

.jpg.png)

Munchkin’s position was that its product did not constitute an infringement because it was based on pre-existing designs for baby baths and that as result, Schnuggle’s RCDs were invalid, and their claim relating to unregistered design right was not substantiated because the designs relied upon were commonplace.

Were RCD-196 and RCD-793 valid and did the “Sit and Soak” infringe?

The IPEC held that Shnuggle’s RCD-196 was a valid design but concluded that the “Sit and Soak” did not infringe because it resulted in a different overall impression upon the informed user.

In assessing the claim for infringement of RCD-196 the Court considered the implications of using CAD images in a registered design, and the impact that the use of such images has upon the scope of protection of the resulting design registration. The Court applied the Supreme Court decision of 2016 in PMS International Limited v Magmatic Limited (the Trunki case) and held that the informed user would perceive the green shading present in RCD-196 as part of the design; therefore the scope of protection was limited accordingly. This reiterates the fact that line drawings are preferable to CAD images, as the shading in CAD images can narrow the scope of the resulting registration and have a significant impact upon the proprietor’s position to enforce their registered rights against third party designs.

Perhaps surprisingly, given the position it took with respect to RCD-196, the Court held that RCD-763 was invalid due to the existence of the earlier RCD-196, which had the same overall impression on the informed user, i.e. RCD-763 lacked individual character over the earlier RCD-196. Essentially the Court held that the differences between RCD-763 and RCD-196 namely the removal of the handles, the lack of colour, the addition of a back pad and the differently shaped bum-bump, were insufficient to render RCD-763 a design which would create a different overall impression. This is a reflection of the fact that changes to products may not be sufficient to create a design which has a different overall impression, so advice should be taken from a Design Attorney from the outset.

Unregistered Design Infringement

In respect of their unregistered design right claim, Schnuggle relied upon six designs relating to certain elements of the first and second versions of its baby bath products, and claimed that each element enjoyed unregistered design right because they constituted “part of an article”. Munchkin submitted that the elements relied upon by Schnuggle were in fact an “aspect of the shape or configuration…of the whole or part of an article”. Following amendment to Section 213 CDPA an “aspect” is no longer capable of protection. The Court agreed with Schnuggle and provided a useful definition of a “part of an article” stating that for the purposes of Section 213 CDPA it is “an actual, but not abstract part which can be identified as such and which is not a trivial feature…assessed in the context of the article as whole”.

The Court held that two of the six elements relied upon by Schnuggle were original but held that only one of the six elements was not commonplace, namely Design 1 as set out below. The element relied upon by Schnuggle is everything below the AA line; features coloured pink were excluded:

.jpg.png)

The next step was for the Court to consider whether Design 1 was copied. According to Section 226(3) CDPA “Reproduction of a design by making articles to the design means copying the design so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to that design”.

The Court held that whilst Munchkin had copied part of Design 1 it had not copied it exactly or substantially. Therefore, the claim for unregistered design infringement was dismissed. The language used by the Judge was not particularly clear when considering this issue. She concluded that copying had taken place in respect of the “shape of the sides of the tub below line AA” (as above) but held that such copying did not constitute copying of the whole of Design 1 “exactly or substantially”.

The decision in respect of unregistered design right is useful because it defines what constitutes a part. The question remaining is if Schnuggle had separated Design 1 into further parts from the outset by claiming the “shape of the sides of the tub below line AA” as a part, would their claim have succeeded or would the Court have held that such a part was commonplace or trivial? It is certainly clear that unregistered design right infringement claims require a significant amount of consideration and strategy and the various “parts” of a single product that a Claimant may seek to rely upon should be defined precisely from the outset.

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/SearchServiceImages/2025-07-15-13-45-36-518-68765b80ef1adb907742f663.jpg)

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/SearchServiceImages/2025-07-15-13-28-49-826-687657911772065ab8f1e3d6.jpg)

/Passle/6130aaa9400fb30e400b709a/MediaLibrary/Images/2024-05-16-11-37-11-800-6645efe75f1e870076120de2.png)